William Burnett Benton is born April 1, 1900 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Charles William Benton, a Congregationalist clergyman and college professor, and the former Elma Hixson, a county school superintendent. His father dies when he is 13, and his mother takes the family to Montana to clear ground for a homestead. William works summers on the 300 barren acres his mother buys.

Benton receives his A.B. from Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. His ability to write leads him to Chair the Yale Record. "He worked his way through [Yale] as a high-stake auction bridge player. While denying reports that he cleared $25,000 a year, he told a friend that 'it's a demonstrable fact that for 10 years, I was one of the 10 or 20 best card players in the world.'" (New York Times Obituary)

Benton marries Helen Hemingway, a Connecticut school teacher.

Benton starts Benton & Bowles Inc. Agency in 1929 in New York City. The advertising agency flourishes during the Great Depression, due, in part, to innovations in radio entertainment programs sponsored by advertisers. Benton retires from advertising in 1935.

In addition to pioneering market research, 'in his early years in advertising, radio was just coming into its own. And Benton was personally responsible for many of the program formats and advertising techniques that are still with us today.' Benton is credited with introducing the studio audience and signs to direct it to applaud, box-top offers, as well as commercials with singing and sound effects.

— Nicholas Johnson, Memorial Tribute, June 11, 1973

Benton joins the University of Chicago as a public relations expert and fundraiser at the behest of President Robert Hutchins, beginning an eight-year association with the University.

Benton agrees to spend several months on a study of the potential use of public relations by the University and produces a final document that is in every respect a path-breaking, if somewhat disturbing, approach to “selling” a university. By utilizing data from interviews undertaken in seven midwestern cities, Benton applies sophisticated, state of the art advertising techniques to an analysis of the University’s image outside its own walls.

Benton helps the university pioneer in educational radio and educational movies. Benton sees the University’s experiment with a radio discussion program, “The University of Chicago Round Table,” which started modestly in 1931, as an early success in the perennially losing battle to devote broadcasting to the public interest it is chartered to serve. The series proves its great potential for spreading the reputation of the University.

It was from the University of Chicago that Benton begins the organizing of the Committee on Economic Development with U of C Trustee, Paul G. Hoffman.

Benton purchases the Encyclopaedia Britannica from its then owner, Sears, Roebuck and Company, giving the University of Chicago a beneficiary interest in the profits. (By the year after Benton’s death in 1975, the accumulated royalties to the university amounted to $47.8 million.). Still determined to find ways of enlarging the audience for scholarly research by bringing an understanding of that research to public attention, Benton seeks ways of relating the Britannica to the University of Chicago, and both to the growing interest in movies and radio as disseminators of new knowledge.

Poor as a child, he set out to make money—and became wealthy and famous before middle age. At 35, he retired [from advertising] to devote the rest of his life to ‘something worthwhile,’ as he once put it…Bill Benton revealed a casual and utilitarian attitude toward money as an implement rather than a goal…I remember a number of occasions on which he rather startled his own Board of Directors at Britannica by making similar detached statements about money. ‘There is only one reason why EB should show a profit,’ he would say, ‘and that is to enable the continuing improvement of the educational and editorial excellence of its products.'

— Robert P. Gwinn, Memorial Tribute, June 11, 1973

Benton asks Mortimer J. Adler and Robert Hutchins to edit a set of “great books” to be published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. The Great Books Program plays a dual role in promoting an interest in ideas among citizens whose careers had not involved college training and in publicizing the values of great university teaching and research and the role of the University in public education. The 52-volume set of Great Books of the Western World is published in 1952.

Although Benton’s efforts to publicize the University through articles in popular magazines and newspapers are a remarkable success, his greatest success, perhaps, is in the further development of radio programs that used University faculty and sought to make university research intelligible to lay audiences, including “The Human Adventure.”

From one perspective, at least, William Benton’s career is a study in the complex relations between the specialized, even arcane interests that are now characteristic of academic research in all areas of human knowledge and the needs of a democratic society which must be asked to respect that research, sustain it with public and private funds, and appreciate its essential utility. Convinced that there were no insuperable barriers between the highest levels of knowledge and the capacity of the public to understand, he devoted his career to creating new pathways…

A democratic society could indeed be built on knowledge made available to all, not the preserve of a special class. The responsibility of democratic leadership was to make that transmission possible. The benefits of research are ultimately mass benefits, to enrich the world and to generate the continuing process of research.

— William Benton, A Public Life (University of Chicago, 1986)

Vice Chairman, Board of Trustees, the Committee for Economic Development, a national coalition of business leaders. In October 1944, Benton delivers a clarion call in the pages of Fortune magazine, and offers a forward-looking agenda to deliver a more peaceful and prosperous future for all Americans—not just a few. “The good of all—the common good—is a means to the enduring happiness of every individual in society and is superior to the economic interest of any private group,” Benton wrote.

He leaves the University to become Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs, beginning yet another career in the application of his talents as a publicist to the national interest. His assignment is to pick up the pieces of the wartime agencies OSS, OWI, and OIAA and change them into an instrument useful to postwar foreign policy. Benton’s varied interest in policy-making organizations enable him to bring together leaders in business, governments, and academia. Under his direction the State Department begins the “Voice of America” radio broadcasts, the U. S. Information Offices, and UNESCO. Howland H. Sargeant in a June 11, 1973 memorial tribute, calls Benton “Vigorous champion of worldwide freedom of information.”

Benton’s sense of the need to develop intellectual interchanges on a broader scale than had existed before the war led him to support such innovative ventures as the Fulbright Act with its Fulbright international educational exchange programs.

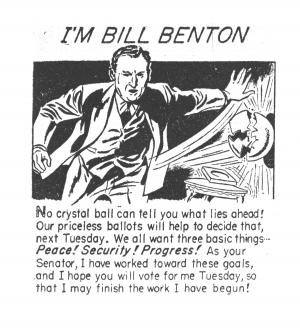

Chester Bowles, then governor of Connecticut, appoints Benton to fill a vacant seat in the US Senate. Benton runs successfully in 1950 for the remaining two years of the term.

A determined critic of Joseph McCarthy, the Wisconsin Repulican and anti-communist crusader, Benton proposes the motion to expel him from the U.S. Senate, which finally censures McCarthy in 1954. On television, when asked if he would take any action against Benton's reelection bid, McCarthy replied, "I think it will be unnecessary. Little Willie Benton, Connecticut's mental midget keeps on... it will be unnecessary for me or anyone else to do any campaigning against him. He's doing his campaigning against himself."

He was the first to foresee the role that radio would play in politics. Many years later, he would be one of the first to use television in his own successful campaign for the Senate.

—Nicholas Johnson, Memorial Tribute, June 11, 1973

Benton campaigns and loses his bid for re-election in 1952. He turns to growing Encyclopaedia Britannica through expansion, including the publication of major foreign encyclopaedias, and acquisition of an educational film maker, which became Encyclopaedia Britannica Films, Inc. He goes on to acquire G. & C. Merriam Company (Webster’s dictionaries) and Frederick A. Praeger Inc., a publisher of art books.

President Kennedy appoints Benton as United States representative to UNESCO where he serves until 1969. Senator J. W. Fulbright said of Benton, “He was deeply interested in the work of UNESCO and recognized that good international relations depend upon factors other than from military might.”

Prime Minister and Mrs. Harold Wilson receive Senator and Mrs. William Benton and Marjorie and Charles Benton at No. 10 Downing Street at a reception given by the Prime Minister and Mrs. Wilson to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Encyclopaedia Britannica.

William Benton dies on March 18, 1973. In the June 11, 1973 memorial tributes, Harold D. Lasswell said: “The life of William Benton was a controlled explosion.” Nicholas Johnson, FCC Commissioner (1966-1973) said: “Throughout this zig-zag life, however, there runs a thread. For most of what Bill Benton did involved, in one way or another, the communications process. And much of the history of mass communications in America shows his hand.”

Below are excerpts from William Benton: A Public Life (The University of Chicago, 1986)

Benton devoted large portions of his income and the income from Britannica stock to the support of philanthropic activities, especially those concerned with communications and education. His experience at the University had convinced him of the importance of organized research as the essential ingredient in the promotion of a stable future world. His experience in advertising and politics had given him the confidence to commit himself to an educated and enlightened public as the base for modern democracy…

He was impatient with the kind of timidity that would keep a man from living up to his fullest potential for fear of making mistakes. ‘The man that never made a mistake never made anything,’ he was fond of quoting. Sometimes he urged associates to ‘make more mistakes.’

He was impatient with perfectionists and the unceasing quest for perfection, which he considered unnecessary as well as unrealistic, and worst of all, a waste of time. 'Improvement, yes; perfectionism, no.'